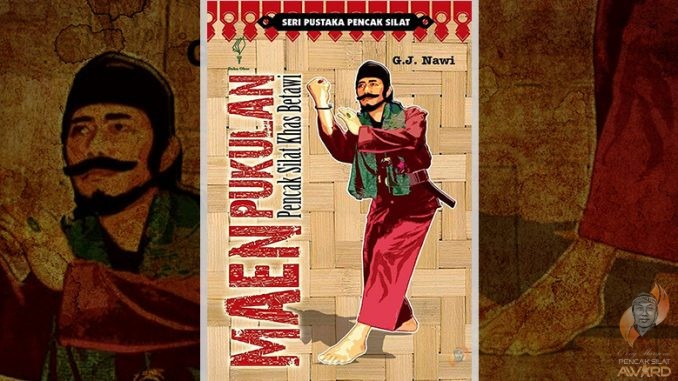

Gusmanuddin Natawijaya, Maen Pukulan: Pencak Silat Khas Betawi (Fist-play: the pencak silat of Betawi)

Jakarta: Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia, 2016, 342 p.

Few books are dedicated to the phenomenon of martial initiations in the Malay world, generally known as pencak silat. The first serious work on this topic was published by O’ong Maryono in 1998, and since then, academic researchers have investigated martial initiations in several regions: Central Java (Grave 2001), peninsular Malaysia (Farrer 2009), West Java (Wilson 2015), Banten (Facal 2016) and through comparative research about martial arts’ music in several Malay regions (Paetzold and Mason, 2016).

Natawijaya’s book on the martial practices of the extended Jakarta’s region is a precious contribution to this field of research. It is the first volume of a book series in Indonesian funded by the O’ong Maryono Pencak Silat Award, a foundation created in 2014 by Rosalia Sciortino, the wife of O’ong Maryono, the famous silat practitioner and intellectual who passed away in 2013. My book is published as the second volume of this collection (Facal 2016) but I have never met Natawijaya in person, as he has rarely promoted his book – following the ethos of the silat world from which he is originated.

Although his work is not intended to provide anthropological analysis, it is based on extensive ethnography and a deep knowledge of the historical and socio-cultural background of the pencak silat in Jakarta. For more than three decades, he conducted interviews and engaged in participatory observation. This experience allows him to gain a detailed understanding of both specific techniques and body mechanics of the martial practice. At the same time, his comparative approach provides him with a level of objectivity that the practitioners’ reports about the art generally lack. He also made good use of a number of social networks, including the Forum Pelestari Pencak Silat Tradisional Indonesia (Forum of the Preservers of Indonesian Traditional Pencak Silat, FP2STI), which was developed by young adepts of martial practices in Jakarta who have engaged in a collective empirical investigation over the last dozen years. While some may find the discussion of interviews conducted over the internet and on facebook surprising, it must be considered within the context of this wider set of collaborations. These combined methods have been used to advance an extensive research agenda, but “only” 25 schools/streams have been selected (among 317 that he has counted in the region – almost a half of the total number of streams he evaluates in the archipelago) for this book.

The book consists of eight chapters. The first chapter describes the main contemporary challenges faced by maen pukulan practitioners. These are the massive diffusion of foreign standardized martial arts imported from Japan and the United States and, as a reverse effect, the political attempts of the local authorities to promote Betawi’s culture which have resulted in the re-shaping of folkloric content. By contrast, he describes the slow and progressive formation of Betawi’s identity (since the second half of the 19thcentury), while pointing out its current fluidity. This flexibility is marked in the martial field, through a high capacity of the schools to integrate foreign elements. It is also highlighted by the multiple collaborations of the founding masters of maen pukulan with Chinese practitioners, and cooperation between initiates originating from working-class migrants who came from different regions of the archipelago. It is equally stressed by the plural modes of initiation: practitioners use to be initiated by masters who achieved to defeat them or by their father-in-law. Finally, this flexibility is seen in the highly syncretic dimension of almost all the schools’ Muslim religious backgrounds which involve the veneration of ancestors, animistic figures (mainly natural and animal ones), mystical practices (like kebatinan and hikmah), and authority being embodied by women and feminine figures. These syncretic dimensions contrast with the recently positioning of several Betawi masters as defenders of puritanical Islam, in a context of a national scale “political Islam”.

The second chapter provides a useful diachronic contextualization of the schools’ development, the historical role of the local strongmen (jago) in national construction and regional politics, and a detailed presentation of the main figures of maen pukulanBetawi’s universe. The next three chapters are dedicated to the presentation of twenty-five streams: five for the coastal and archipelagic region of Jakarta, ten for the inner part of the capital, and five for the periphery of the city. The discussion of each stream includes the locality and its toponymic’s background, history, technical structure, rituals and the main characteristics concerning its martial strategies. The localities of the streams are illustrated by photographs that he has collected from the KITLV (Leiden University, the Netherlands) and Indonesian national library. Pictures of the masters, their graves and techniques give additional insights to the deep meanings of the streams.

The first of the three final chapters provides a useful presentation of the practices that encompass or/and influence Betawi’s maen pukulan: wedding ritual palang pintu, stick fighting ujungan, Malay poetic form pantun, dances tari silat and ibing penca, as well as theater lenong. The next chapter offers an extensive list of the accessories and weapons used by the practitioners. It is very detailed and well illustrated. Finally, a conclusion, glossary and bibliography end the book.

As a popular book, understandably, there is little actual analysis. However, its clear structure provides readers with a means to easily compare the streams and their technical, ritual and cosmological characteristics. The numerous interviews (around forty five) with numerous masters, initiates and political representatives of the groups contribute to the understanding of the connections between the practitioners. These links determined in large part conditions that contributed to the development of the schools. The area is a great melting pot given complex overlay of local animist practices (seen in techniques inspired by the observation of the natural environment, the reference to animal figures, many ritual elements, and cosmologies), persistent reference to the Tarumanagara (4th – 7th century) Hindu Buddhist kingdom’s legacy, Chinese kuntao practices, influences of the Dutch colonial policies (particularly during the 19th and at the beginning of the 20th century), Japanese inflections during the occupation period (1942-1945) and recent influences from the West.

This holistic aspect of maen pukulan could have been enhanced more explicitly, particularly by avoiding the use of misleading categories such as “art” (seni), and by placing the chapter about the connected practices in the first part of the book. External points of view are also present in the categorization that the author uses by distinguishing between self-defense, art, sport, and mental/spiritual dimension. Such categories are constructed by the national federation (Ikatan Pencak Silat Indonesia); strangely, it uses imported references as a way to standardize local practices.

Given current efforts to win pencak silat’s adoption on the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage (possibly in 2019) such point deserves careful consideration by martial arts studies scholars and silat specialists. This may help to prevent the folklorization of these practices which Natawijaya might be rightly criticized for advancing. In this respect, such a study is not only a wonderful basis for ethnological research and a must read for the understanding of maen pukulan Betawi, but also a key reference for a reflection of the political anthropology on the future trajectory of martial practices in Indonesia.

Reviewed by Gabriel Facal

Postdoctoral researcher and associate member at Institut de recherches Asiatiques (IrAsia), UMR 7306, Aix-Marseille Université, France.

Reference:

Facal, Gabriel. 2016. Keyakinan dan Kekuatan. Seni Bela Diri Silat Banten (Strenght and faith. Silat martial art in Banten). Jakarta: Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia.

Farrer, Douglas. 2009. Shadows of the prophet: Martial Arts and Sufi Mysticism. Dordrecht: Springer.

Grave, Jean-Marc de. 2001. Initiation rituelle et arts martiaux – Trois écoles de kanuragan javanais. Paris: Archipel/L’Harmattan.

Paetzold, Uwe and Mason, Paul (eds.). 2016. The Fighting Art of Pencak Silat and Its Music: From Southeast Asian Village to Global Movement. Leiden: Brill.

Wilson, Lee. 2015. Martial Arts and the Body Politic in Indonesia. Leiden: Brill.